Wirecutter’s new take on “The Real Reasons Your Appliances Die Young” has a big reveal: “the mythical 30-year-old fridge in Grandma’s basement ... has been the exception all along.”

The author spoke with service technicians, designers, engineers, trade-organization representatives, and salespeople who say that decade-spanning durability “was always the outlier, not the norm.” One long-time appliance repair veteran says that appliances made three or four decades ago lasted only 10 to 15 years. The article then cites data from manufacturers showing today’s appliances last an average of 9 to 14 years.

It may be a surprising point, but it’s largely consistent with Energy Department survey data we’ve reviewed. There are good products and bad products, but the average lifetimes haven’t actually changed much. You remember a lemon today and a workhorse of the past.

All right, interesting point made, article over? No. After showing that today’s appliances last about as long as they used to, the article still has 3,700 more words to find out why they “die young.” Huh?

Series of false claims on energy efficiency standards

Wirecutter finds numerous reasons an appliance might not last as long as we want, including “price wars driven by global trade” and “people’s own desire for increasingly sophisticated features requiring complex components that are far more likely to fail.” Those factors may indeed contribute to poor durability in some products. But Wirecutter’s first target? Government regulations, and specifically efficiency standards.

The article presents several arguments for why efficiency standards might hurt durability. None hold up to basic scrutiny.

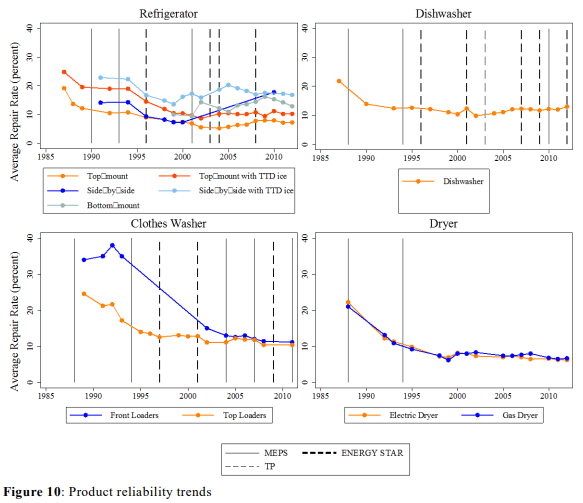

A video report embedded in the article says: “Every appliance tech I spoke to blamed federal regulations passed in 1987.”

Did durability take a hit from those first standards? Wirecutter doesn’t actually present any data. Fortunately, a study from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory examined this very question. It reviewed Consumer Reports survey data of readers who had purchased a new appliance in the previous five years, asking if they had “ever repaired or had a serious problem that was not repaired,” generating a “repair rate” statistic. It turns out that the durability of these four products improved after the first standards took effect (“MEPS” in the charts below refers to a new efficiency standard taking effect):

Wirecutter never mentions the study. And it never mentions the Energy Department’s survey data, either. Instead, the first person it quotes criticizing standards is the same appliance repairman who earlier said that models of previous eras lasted basically as long as today’s. Which way is it?

Next up, Wirecutter says that “to meet any new standard, appliances often move from analog parts to digital components, such as computer circuit boards.” You only have to look elsewhere in the article to see why this gets the history mixed up. It recommends you consider purchasing a refrigerator that is a simpler, “fully analog” model. But to be sold, any model, including that one, must meet the efficiency standards in place today. In other words, products often include popular digital features, and electronic controls can be used to improve efficiency performance, but standards have generally not required digitalization.

Wirecutter’s next argument: “Standards have also prompted changes that max out efficiency but potentially reduce repairability.” It says that refrigerator cooling systems used to have copper components that could be easily repaired, but “now they’re made mainly of aluminum, which more efficiently removes heat (it also resists corrosion and is more affordable and lightweight).” Wirecutter has now revised this text, arguing that aluminum “resists corrosion and is more affordable and lightweight, factors that can support more efficient heat removal.”

Take just a minute to Google it, and you’ll learn that copper is in fact a better conductor of heat than aluminum. We reviewed the Energy Department’s analyses on past refrigerator standards, and sure enough it never argues that using aluminum for these parts provides better efficiency than copper. A former appliance manufacturer engineer I spoke to pointed to the corrosion issue as the primary reason for the switch from copper to aluminum.

Wirecutter’s final efficiency argument concerns washing machines. It says that because of “regulation-driven design changes,” manufacturers use more lightweight plastic components instead of metal parts, giving the example of a tub in a washer taking less energy to move. It says that when plastic components break, they must be replaced, not repaired.

We looked at numerous very-efficient washing machines (ENERGY STAR certified models) sold today; they overwhelmingly use durable stainless-steel tubs. In fact, the Energy Department’s analysis in its most recent standards for the product specifically said that this material is used because it can handle high spin speeds, a key energy efficiency feature because it reduces energy use in drying. In other words, a washing machine with a plastic tub would generally be less energy efficient.

Certain models and popular features may have durability problems

Wirecutter gets certain things right. For any given appliance, some brands and models will be more durable than others, and some optional features (such as ice dispensers in refrigerators) can be prone to problems. The article also makes an important point that consumers’ replacements of some products have become more frequent as inflation-adjusted purchase costs have decreased significantly, while repair costs have gone up.

But Wirecutter’s claims that efficiency standards are causing durability problems just don’t hold up.